Meet Your Tour Guide – Emily Kimi Witherow

Hi there! My name is Emily (Gallery Attendant and Exhibition Assistant, 2024-25), and you’ll be hearing my voice as I guide you through 10 of my favourite objects, photos, and stories hidden within the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection.

I grew up in Ottawa, on the traditional, unceded, and unsurrendered territory of the Anishinaabe Algonquin People. Mining history may seem like dry reading to some, but I became fascinated with the nineteenth century stampedes after researching the genocide of California Indigenous Peoples during the California Gold Rush. The series of gold rushes that swept across the world like wildfires after 1848 were cataclysmic moments of collision, conflict, and colonization, but also of adaptation, resilience, and community.

The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation, whose traditional territory encompasses the Klondike goldfields, refer to the Klondike Gold Rush and the decades that followed as “the Great Upheaval.” The stampede wasn’t a single event, but the start of a long process of environmental, economic, and cultural change that fundamentally altered people’s relationships with each other and the land. This was not the first time Yukon First Nations adapted to newcomers, but the rapidity and extent of change that accompanied the Klondike Gold Rush overshadowed all events that preceded it.

This Highlights Tour aims to highlight Indigenous sovereignty, dispel myths about the glitz and glamour of the Klondike, and emphasize the environmental impacts of placer gold mining. Thank you for joining me, and I hope you enjoy your visit!

1. Imagining Gold Mountain

Welcome to the 360-degree virtual tour of the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection! From the fifteenth century onwards, the myth of the golden city of El Dorado motivated Europeans to explore and colonize Indigenous territories throughout what is now called the Americas.

When gold was discovered in California in January 1848, a new wave of “gold fever” spread around the world. With each new discovery, places like Australia, Aotearoa/New Zealand, British Columbia, Yukon, and Alaska entered the public imagination as sites of adventure and extraordinary wealth, and people’s thirst for gold grew. In Southern China, California and subsequent gold rush locations became known as Gold Mountain (“gum saan”), representing both the gold mines and migrants’ hope for a better life.

While the rushes naturalized what was seen as gold’s inherent economic value, the prioritization of gold mining was a cultural choice with severe consequences. Between 1848 and 1900, over half a million men and women left their homes in search of gold. More often, they found disappointment, hardship, and labour. For the Indigenous peoples whose ancestral, traditional, and unceded territories included these new goldfields, the gold rushes brought chaos, environmental destruction, and social upheaval. Ultimately, very few prospectors became rich, and the reality of Gold Mountain was far less glamorous than imagined. The Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection seeks to highlight these human experiences within the broader context of migration, colonization, and cultural clashes.

2. John Grieve Lind

The Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection highlights the little-known story of Phil’s grandfather, John (Johnny) Grieve Lind, a railroader-turned-prospector who was one of the few to get rich in the Yukon. Born in 1867 to a farming family in Ontario, Johnny’s adventurous spirit led him to leave school and work as a railroad engineer in the United States. In 1894, a coin toss inspired his journey north in search of gold.

He endured a 5-week trek over the Chilkoot Trail and down the Yukon River, arriving in Forty Mile, a small mining community north of modern-day Dawson City, in June 1894. There, he worked 12-hour shifts mining other people’s claims for half an ounce of gold per day, learning essential mining techniques and how to register claims.

When gold was discovered on Bonanza Creek in August 1896, Johnny and his mining partners, John Crist and Skiffington Mitchell, moved to the confluence of the Yukon and Tr’ondëk (Klondike) Rivers. There, they purchased and staked several claims, some of which were exceptionally rich. By May 1897, Johnny employed 200 men working in 10-hour shifts on one of their claims, 26 Above Bonanza, which once yielded over $50,000 in gold in a single day. An avid reader, Johnny avoided the 3 pitfalls of the successful miner: liquor, gambling, and women. After years of hard work, Johnny returned to Ontario in 1902. Although he never saw the Yukon again, Johnny’s stories lived on through his family – and now, through this collection.

3. Shaaw Tláa (Kate Carmack)

Can you spot Shaaw Tláa (also known as Kate Carmack) in this image? While historians highlight her brother Keish (Skookum Jim Mason), and husband George Carmack, Shaaw Tláa – once known as the richest Indigenous woman in the world – is often overlooked in historical narratives.

Born to a Tlingit-Tagish family near present-day Lake Bennett, Shaaw Tláa belonged to the Daḵł`aweidí (Killer Whale) clan. After her first husband and infant daughter died around 1886, she married George Carmack, an American widower and prospector. For years, Shaaw Tláa’s knowledge and skills were vital to George’s gold hunt leading up to their major discovery in August 1896. The story about the discovery of gold changes based on the teller, but George’s nickname, “Lying George,” hints at doubts surrounding his claims. During the subsequent gold rush, Shaaw Tláa sold hand-sewn mittens and hats to miners and worked the family claims on Bonanza Creek, which by one estimate yielded $2.5 million in gold.

In 1898, the family traveled to Seattle and San Francisco to enjoy their newfound wealth. However, while Shaaw Tláa and their daughter, Graphie Grace (Aagé) stayed at his sister’s farm in California, George returned to Dawson and married a French woman named Marguerite Saftig. He later disavowed his marriage to Shaaw Tláa and denied any connection to his Tagish relations. Shaaw Tláa sued George for divorce on the grounds of desertion and adultery, but the courts refused to recognize their Tagish marriage, leaving her without her share of their fortune. She also lost her daughter; at the age of 17, Graphie moved to Seattle and married Marguerite’s brother, separating her from her Tagish family. Shaaw Tláa passed away from influenza in 1920.

Shaaw Tláa was a catalyst and contributor to the Klondike Gold Rush, a fact which was recognized by her induction into the Canadian Mining Hall of Fame in 2019 – 20 years after the other Klondike discoverers. Her legacy lives on through the Skookum Jim Friendship Center and the squirrel fur cape she sewed after returning home in 1900, which is on display at the MacBride Museum of Yukon History.

4. The Klondike Official Guide (1898)

The name “Ogilvie” is everywhere in the Yukon – it’s the name of a river that stretches through Tombstone National Park, a mountain range outside Dawson City, even a street in downtown Whitehorse. These landmarks all commemorate William Ogilvie, the Canadian surveyor and bureaucrat who wrote this book, The Klondike Official Guide, and who ended up playing a key role in Yukon history.

Born in 1846 in Upper Canada, William Ogilvie began working as a Dominion Lands Surveyor in 1876, mapping township boundaries in the Prairies. Ogilvie’s work was part of Canada’s broader nation-building efforts at the time, aimed at Western settlement and resource exploitation. From 1885-1886, he surveyed the British Columbian mountains for the Canadian Pacific Railway. A year later, Ogilvie joined George M. Dawson’s Yukon expedition, tasked with surveying the Alaska-Yukon boundary along the 141st Meridian. While Dawson and Richard G. McConnell identified mineral deposits, Ogilvie’s precise mapping was vital in asserting Canadian control over the region.

Following the Klondike gold discovery, global demand for reliable information surged. In response, the Department of the Interior republished Ogilvie’s Yukon notes as The Klondike Official Guide (1898). This guide became a key resource for miners, detailing travel routes, essential supplies, and mining laws.

Through publications, lectures, and political advocacy—many of which are housed in the Phil Lind Collection—Ogilvie promoted the Klondike to investors and politicians. Appointed Yukon Commissioner from 1898-1901, William Ogilvie went on to govern the territory during its most turbulent period, shaping the region’s development and strengthening Canadian authority in the north.

5. Łkóot Déi (Precious Place)

Eric A. Hegg’s photo of prospectors ascending the 53 km-long Chilkoot Trail in 1898 is one of the most iconic images of the Klondike Gold Rush. Yet long before gold seekers arrived, the Chilkoot Trail served as a key trade route connecting coastal Chilkat and Chilkoot Tlingit (Jilkaat/Jilkoot Kwaan) with interior Athabaskan communities.

Traders transported eulachon (oolichan) grease, dried fish, furs, lichen dyes, and other goods along this path. Tlingit and Tagish families often intermarried, strengthening trade relationships. For the Tlingit, who know it as Łkóot Déi (“precious place”)(shlkoot-day), the trail is home – not a transit route.

Following clashes between the Tlingit and American prospectors over their use of the trail, the US Navy dispatched Captain Lester A. Beardslee to negotiate – with a howitzer and Gatling gun. The trail was opened, but throughout the 1880s, Tlingit guides helped Euro-Americans to cross the pass, charging high fees to “pack” supplies and maintaining control over trail access.

The Klondike Gold Rush transformed the Chilkoot Trail. By the end of 1898, 20,000-30,000 stampeders (including 1,500 women) traveled this ‘poor man’s route’ to the Klondike goldfields. Travelers were required to carry a year’s supply of goods and pay customs duties on non-Canadian items, turning the trail into a crowded industrial corridor. To reach the summit, stampeders could choose the longer Peterson Route or ascend the Golden Staircase—1,500 steps carved into a 45-degree glacier. Indigenous packers tried to maintain their foothold, but new technologies like aerial tramways and horse-powered windlasses cut into their monopoly. By 1900, the newly completed White Pass and Yukon Route Railway further reduced foot traffic. The Chilkoot Trail is now a National Historic Site of Canada and remains an integral part of the traditional territories of the Carcross Tagish First Nation and the Taku River Tlingit First Nation.

6. The Summer of 1898

Every year thousands of tourists visit Dawson City, nicknamed “The Paris of the North,” and enjoy the town’s colourful storefronts, vintage sternwheelers, and dusty boardwalks. While it’s true that in summer 1898, Dawson boasted a cosmopolitan population of roughly 17,000, the reality was far from Parisian glamour – in fact, one miner called it a “nasty stinking mudhole.”

Mudhole is right; Dawson City lacked running water, sewage, telegraphs, or electricity until late 1898. That spring, ice jams flooded the town, washing waste into the streets and forcing the police to dig drainage ditches. Between 1897 and 1899, annual fires repeatedly destroyed the town’s business sector, leaving only ashes behind. Mining work was also limited – paying claims were already staked, a 10% gold royalty slowed operations, and an unusually dry summer hampered sluicing. Hundreds of unemployed miners lived in shacks above town, known as ‘Unfortunates’ Row,’ surviving on bread and beans. Poor diets and bad hygiene led to a typhoid epidemic that summer, overwhelming charitable hospitals like St. Mary’s.

As early as June 1898, newcomers began leaving in droves. By December 1898, a police census counted just 4,236 residents in Dawson – the Klondike bubble had officially burst. Ultimately, Dawson did become a “modern” city, but not until the next year, when the White Pass and Yukon Route Railway improved transportation and enabled the cheap import of luxury goods and services.

7. Industrial Mining

From 1896 until the 1950s, placer gold mining was the single largest contributor to the Yukon’s economy. Placer gold, carved out of rock formations by erosion, accumulates along creek beds and hillsides. Placer mining involves locating the “pay streak,” (the layer of gold concentrated near the bedrock), removing everything above the deposit, and separating the gold. In the Yukon, this process is complicated by permafrost – a layer of permanently frozen soil between us and the bedrock.

Early prospectors were limited to mining shallow creek beds, but during the winter of 1887-1888 William Ogilvie suggested a technique used in Ottawa to reach defective waterpipes in the winter: using fires to melt holes in the frozen ground and sink shafts to the bedrock below. By 1900, steam boilers replaced this slow “burning-down” technique.

Like previous gold rushes, individual miners gradually gave way to large-scale mechanized operations. As early as January 1898, the government allowed companies to lease dozens of claims at a time, called concessions. Despite protests, by the mid-1910s, businessmen Joe Boyle and A.N.C. Treadgold controlled large amounts of land through the Canadian Klondyke Mining Company (CKMC) and Yukon Gold Company (YGC), respectively. Between 1899 and 1902, over 1,000 km of Yukon waterways were granted through concessions. Using high-powered water hoses and massive dredges, these companies consumed valleys and creeks, stripping them of trees, destroying animal habitats, and polluting the groundwater. By 1913, at least 13 dredges operated in the Yukon. In 1923, CKMC and YGC merged to form the Yukon Consolidated Gold Corporation (YCGC). Today, visitors driving into Dawson City can still see the lasting impact of this industrial mining: six-foot tall worm-like piles of rock, left by dredges, which line the roadside.

8. Chief Isaac

Chief Isaac, standing here with Chief Don-a-wok of the Chilkoot people, was the Chief of Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation during the Klondike Gold Rush – or the Great Upheaval, as they know it. A member of the Wolf Clan, he married Eliza Harper, daughter of Hän Chief Gäh St’ät, and had four children. Canadian-American writer Tappan Adney described him as a man who carried himself with “conscious self-respect,” and had a “flashing eye” that conveyed mastery and shrewdness.

After gold was discovered and stampeders overran Tr’ochëk, an ancestral Hän salmon fishing camp, Chief Isaac worked with the Canadian government, Anglican church, and police to secure a permanent land base for his people. Fearing cultural loss and conflict, Chief Isaac moved his community downriver to Moosehide Village, and entrusted important Hän songs and dances to Alaskan relatives across the border line for safekeeping.

Despite his relocation, Chief Isaac maintained ties with Dawson’s settler community for 30 years. A skilled speaker, he addressed crowds during events like Discovery Day and Victoria Day, reminding them that they prospered at the expense of the original inhabitants of the Yukon. He often posed for photos with tourists in moose-hide regalia and used local and international newspapers to criticize settlers’ overhunting and land seizure. Every Christmas, Chief Isaac invited Dawson residents to Moosehide for a potlatch, a gift-giving ceremony vital to Hän sovereignty and governance, even though potlatching was banned by the Indian Act until 1951. Still, Chief Isaac was well-liked by Dawson society and even received honorary membership in the Yukon Order of Pioneers.

Today, Chief Isaac is remembered by the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation for his leadership and foresight during a period of profound cultural, social, and economic change.

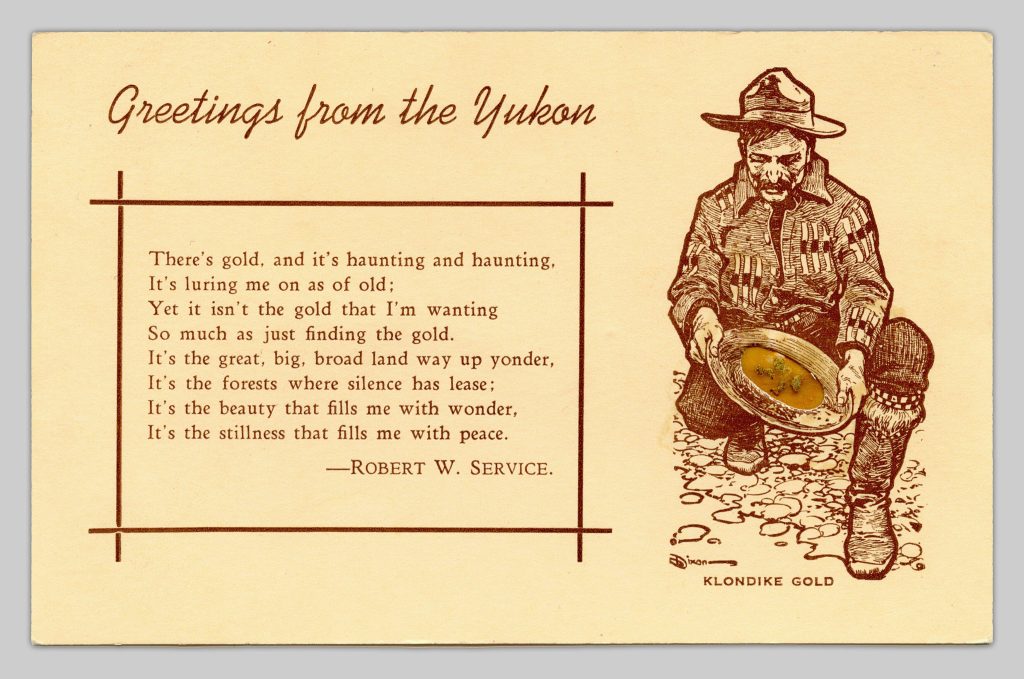

9. The Bard of the Yukon

Known around the world as the “Bard of the Yukon,” famed poet and writer Robert Service was actually born in Scotland and was first inspired not by the Canadian North – but by the American West. When he immigrated to Canada in 1896, he even dressed the part, donning a Buffalo Bill costume, Mexican sombrero, and air gun!

Floating around the west coast, Service worked odd jobs as a ranch hand, orange picker, and railroad worker before securing a banking position in Whitehorse, Yukon, in 1904. It was there he published his first and best-known book of poems, Songs of a Sourdough, in 1907.

In Songs of a Sourdough, Service distilled his fascination with the western “frontier” into vivid poems about saloon shoot-outs and reckless cowboys. He depicted the Yukon as feminized, beautiful, and dangerous, and described the “men who are grit to the core” who could conquer her. Of course, depicting the Yukon as an empty mining frontier overlooks the long and established history of Indigenous Peoples in the area. Despite this, Songs of a Sourdough was an immediate hit, selling out two advance printings before its official Canadian release and leading to the publication of an enlarged American edition a few months later.

Although Service became famous for his Northland poetry, he was acutely aware that he lacked the experiences that he had chronicled in verse and prose. After all, when he arrived in Dawson City in 1908, the Klondike Gold Rush was all but over. Nevertheless, Robert Service is today known as Canada’s national poet and remains one of the country’s most widely read and translated authors.

10. Golden Books

When Phil Lind was just 4 years old, his grandfather, John Grieve Lind, passed away of a stroke. Growing up, Phil often heard stories about his grandfather’s time in the Yukon. Inspired by these tales and encouraged by his father, Jed, Phil began collecting books, diaries, letters, maps, newspapers, and other unique and rare artifacts from the Klondike Gold Rush.

As Phil visited antique stores and rare book dealers across North America, his grandfather’s stories came to life. Phil’s own fascination with the Klondike grew, and over time he amassed a remarkable collection, including 500 books and 1,800 photographs.

These volumes capture both the remarkable and the everyday experiences of those who embarked on the long journey north. Recognizing the significance of their adventure, thousands of travelers documented their challenges, thoughts, and successes in letters, diaries, and memoirs – many of which have ended up in archives like this one. These firsthand accounts help historians to understand the Klondike Gold Rush on a personal scale, and to answer new questions about gender, race, labor, and cross-cultural encounters. Phil’s collection offers a window into the lives of ordinary people caught up in an extraordinary moment – and stands as a testament to curiosity, resilience, and the power of storytelling.